"La musica è la luce, l’anima del film."

- Giovanni Fusco -

|

|

| |

GIOVANNI FUSCO

GIOVANNI FUSCO

S.Agata dei Goti (Benevento) October 10th, 1906 – Rome, May 31st, 1968

Composer, pianist, and conductor.

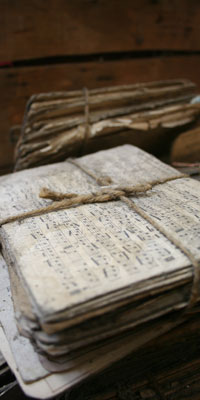

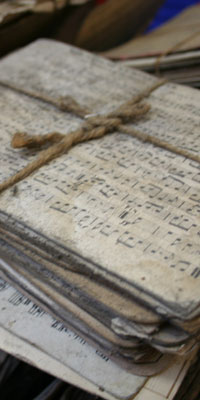

An eclectic and talented musician, he wrote about three hundred compositions, three plays, chamber music of sacred kind and, mostly, sound-tracks for feature films, short films, and documentaries.

His life, from his early childhood, was surrounded by a musical atmosphere. He was born in a large family, his father was Carlo Fusco (from S.Agata dei Goti) and his mother Maria Teresa Folena (from Lucca), he was the youngest of seven brothers, four of which were appreciated musicians. Lorenzo, the oldest, famous tenor, who had been fellow-student of Beniamino Gigli’s, was company with Ettore Petrolini.

Lorenzo, called Enzo, has been great interpreter of the Parthenopean lyric and of the famous patriotic song, as “The Legend of the Piave River”, and also the author of the very famous “Dicite ‘ncello vuje”.

Tarcisio, composer, pianist, and conductor, devoted himself to the world of variety show, and he has been one of the first musicians to devote himself to the connection between music and cinema, conducting orchestras during the showing of silent movies. Finally, Antonio and Romeo, violinist and percussionist, respectively.

For the young Giovanni, since his early childhood, the music is fashion in those days was very familiar: from the popular taste of the world of variety shows, to lyric songs.

At the age of six, his father took him to Rome, from his native region, Campania, to llow him to study. This decision was fundamental for his education; it allowed him to discover and develop his bright and natural musical attitude, through regular studies at the Liceo Musicale of S.Cecilia, where he studied piano under the supervision of P. Boccaccini. Since then, Rome became his adopted city, where he studied, worked, and spent his entire life. Here, when he is only nine, following his brother’s example, he plays the piano during the showing of silent movies, at the Sala Regia of Via Cola di Rienzo, and at the Cinema Corso, earning ten liras per evening. These were important movie theatres, which could afford to hire even an entire orchestra, but, at dinner time, the players used to take a break and a boy, wearing short pants, alone, used to comment with the music of his piano.

This fundamental experience, becomes his first experimental and forming site, which, in the future, will bring him to find a perfect fusion with the world of vision, keeping the integrity of the musical subject, according to its constructive logic; furthermore, updating and completing it through the addition of the most different contributions, to be considered, in the future, a “fundamental character” in the world of music for films. He also used to be, with Goffredo Petrassi and Ennio Francia, one of the singers of San Salvatore in Lauro’s.

After his piano studies, where he graduated very successfully, his education continued at the Academy of Santa Cecilia, where he took organ lessons from Fernando Germani, composition lessons from Riccardo Storti and Alfredo Casella, and conducting lessons from Bernardino Molinari. In 1931, he graduates in composition from the Conservatorio of Pesaro and, in 1942, in conducting from the Conservatorio Santa Cecilia of Rome. Under the supervision of Alfredo Casella, he also improved his piano ability, these studies shared with Adriana Dante, pianist and inseparable companion of his life.

During the years of Fusco’s youth, in the period between the two wars, the Italian music scene was going through an exciting reformation movement, due mostly to the “eighty’s generation”, which included Respighi, Pizzetti, Casella, Malipiero, and a certain number of less important authors. Certainly, Casella was the ensign of this renewal movement, which was hoping to elevate the Italian musical culture, trying to bring it inside a larger European scenery. Casella himself had all the talents of the composer, theoretic, and pianist, and he had deeply understood, clearer than his colleagues had, that the modification of the way of life of the human communities was also modifying the ways and the kinds of their sensorial perception. For Fusco, to meet this great artistic personality was very useful, either for the acquisition of the theoretic basis about the nature of the musician, based on humble and conscious handicraft, even though of a “superior handicraftsman”, like the great figures of the Renaissance, conscious of his function, and for the opening towards what was new, towards a world which was fastly changing, and that makes him, fearless, with audacity, try all kinds of new experiences and experimentations. From this maestro, Fusco will adopt, mostly, his courage and ability to retake other author’s styles, keeping unchanged, in their forms, a clear plasticity of the musical figurations, a deep iconicity, playing among polytonal solutions, rhythmic vibrations, rhythms taken from the most dissimilar musical kinds, such as Fox-Trott, Jazz, and the “consumption music” that, up to those days, had found the hostility of the official academic milieu, and also arriving to introduce some electronic experimentations. During the years of Fusco’s youth, in the period between the two wars, the Italian music scene was going through an exciting reformation movement, due mostly to the “eighty’s generation”, which included Respighi, Pizzetti, Casella, Malipiero, and a certain number of less important authors. Certainly, Casella was the ensign of this renewal movement, which was hoping to elevate the Italian musical culture, trying to bring it inside a larger European scenery. Casella himself had all the talents of the composer, theoretic, and pianist, and he had deeply understood, clearer than his colleagues had, that the modification of the way of life of the human communities was also modifying the ways and the kinds of their sensorial perception. For Fusco, to meet this great artistic personality was very useful, either for the acquisition of the theoretic basis about the nature of the musician, based on humble and conscious handicraft, even though of a “superior handicraftsman”, like the great figures of the Renaissance, conscious of his function, and for the opening towards what was new, towards a world which was fastly changing, and that makes him, fearless, with audacity, try all kinds of new experiences and experimentations. From this maestro, Fusco will adopt, mostly, his courage and ability to retake other author’s styles, keeping unchanged, in their forms, a clear plasticity of the musical figurations, a deep iconicity, playing among polytonal solutions, rhythmic vibrations, rhythms taken from the most dissimilar musical kinds, such as Fox-Trott, Jazz, and the “consumption music” that, up to those days, had found the hostility of the official academic milieu, and also arriving to introduce some electronic experimentations.

The activity of this composer begins following the pre-established canons this profession requires, writing operas, sacred, symphonic, and chamber music. In the early ‘30s, he started to dedicate himself to composition, beginning a symphonic poem inspired to the freed Jerusalem.

In 1934, he starts to write the score for the three-act play by Luigi Chiarelli, La scala di seta, based on the libretto by Mario Casalino. From the same opera, in 1938, the symphonic piece Balletto was created, broadcast by EIAR, and for which he had several contracts.

In 1938, he set to music Via Nuvola 33, a musical play based on a libretto written by Enrico Bassano and Dario Martini.

In 1941, commissioned by RAI, he wrote the Sacred Oratory La cantata profetica, for soloists, chorus, and orchestra, from a text by Ennio Francia, inspired by Psalm 83, it was recorded at the Foro Italico and broadcast on the radio in 1955, conducted by another author. Then, L’ultimo venuto comes, one-act play in music by Dario Martini, commissioned by RAI again, and of this play a recording was made, conducted by Bruno Maderna.

Soon after the end of the war, Maestro Fusco appeared several times, as conductor of concerts of contemporary music, dedicating him self also to the performance of jazz music in American clubs. His remarkable ability of playing at sight, was helping him in doing that; and, he was often proving it during the evenings spent with his musicians friends, where he used to perform for this audience, playing at sight, just printed, the musics by Stokausen or Stravinskij. Beginning these days, other important works deserve to be mentioned, as the Sonata a due, for violin and cello, the Suite Americana, for orchestra, the Sonata a tre, for violin, flute, and clarinet, the Psalm 112, for 4 soloist voices, 2 guitars, and jazz battery, dedicated to Goffredo Petrassi, the Suite for eight instruments, from the movie “Hiroshima mon amour”, the Fantasia da concerto, for violin and string instruments, the Piccolo concerto, for clarinet and orchestra, the Tam Tam of the Animals, for children’s voices and 5 instruments, the Canzone dell’uccellaio, for basso and orchestra, the Sinfonia Italiana, for orchestra, and the unpublished ballet La Rapina, on a subject written by Michelangelo Antonioni, commissioned by the Opera Theater “La Scala” in 1965, and never performed, because of the sudden death of the Maestro. La Rapina is the portrait of the inhabitants living in a neighbourhood outside a city, where the main characters of the ballet go through constant fights and quarrels: “which suddenly start and suddenly end”. Even in this ballet, music is responsible for the intimate expression, deeply plastic, of every represented reality: from the objective one to the one unspeakable of the characters involved. Soon after the end of the war, Maestro Fusco appeared several times, as conductor of concerts of contemporary music, dedicating him self also to the performance of jazz music in American clubs. His remarkable ability of playing at sight, was helping him in doing that; and, he was often proving it during the evenings spent with his musicians friends, where he used to perform for this audience, playing at sight, just printed, the musics by Stokausen or Stravinskij. Beginning these days, other important works deserve to be mentioned, as the Sonata a due, for violin and cello, the Suite Americana, for orchestra, the Sonata a tre, for violin, flute, and clarinet, the Psalm 112, for 4 soloist voices, 2 guitars, and jazz battery, dedicated to Goffredo Petrassi, the Suite for eight instruments, from the movie “Hiroshima mon amour”, the Fantasia da concerto, for violin and string instruments, the Piccolo concerto, for clarinet and orchestra, the Tam Tam of the Animals, for children’s voices and 5 instruments, the Canzone dell’uccellaio, for basso and orchestra, the Sinfonia Italiana, for orchestra, and the unpublished ballet La Rapina, on a subject written by Michelangelo Antonioni, commissioned by the Opera Theater “La Scala” in 1965, and never performed, because of the sudden death of the Maestro. La Rapina is the portrait of the inhabitants living in a neighbourhood outside a city, where the main characters of the ballet go through constant fights and quarrels: “which suddenly start and suddenly end”. Even in this ballet, music is responsible for the intimate expression, deeply plastic, of every represented reality: from the objective one to the one unspeakable of the characters involved.

His main activity, which kept him mostly engaged, was the composition of music for films.

In 1930, the sound movie is introduced in Italy with La canzone d’amore by Gennaro Righelli, with the musical contribution of Cesare Andrea Bixio. Only 6 years after this event, Fusco starts to work in the field of music for films, writing the sound-track for Il cammino degli eroi, a documentary by Corrado D’Errico, where, for the first time, disagreement and opposition elements to the ancient atmosphere of the “white telephones” appear. It is worth mentioning, among others, also the feature film Joe il rosso, by Raffaele Matarazzo, La contessa di Parma, by Alessandro Blasetti, Pazza di gioia, by C.L. Bragaglia, and Questi ragazzi, by Mario Mattioli; these, among the most significant directors of the first decade of the Italian sound movie.

For these works, the contribution of a really creative musician was not necessary, yet, but the first signs of those elements which, in the future, would have become the main musical characteristics of the innovating nature of Giovanni Fusco’s, could be identified, such as the introduction of dance music, popular instruments, intradiegetic music.

Several are the musical advices and contributions that Fusco, in these years, gave to films based on typical comedies of the “white telephones” kind, composing, arranging, and re-writing some sound-tracks for foreign films, such as Duello al Sole.

Fusco’s poetic, still in its early stage, already underlined those stylistic-formal aspects, and a linguistic-musical syntax, which will be codified in a future and mature age, and that can be summarized as follows:

- Eclecticism, can be found among the variety of his composing experiences, of all different kind, lived and fully written by our composer, which all finally end up in his main occupation: music for films. He was associated with “light music” clubs, writing “masters’ songs” (1) as the Ballata del suicidio on a text by Pier Paolo Pasolini for Laura Betti’s show Giro a vuoto, where only few fragmentary notes are accompanied by an obstinate rhythmic left hand of the piano. He practised in the so called “consumerism music” (2) , that kind of music so fashionable in the ‘50s, which we find, deeply adopted, also in his sound-tracks, Fox-Trott, Surf, Twist, Slow. He also took part in the production of radio programs and in the realization of advertisements.(3) As a conductor, he preferred contemporary music, but also moving in the past, and even performing experiences by Bach.

- Essentiality, reduction of the orchestra and of several instruments, sober, in fact reduced to the essential, with a mixture of sounds, sometimes unusual, of just few instruments and, often, adopting popular instruments: in Cronaca di un amore he makes use of saxophones and a piano; in I vinti, solo of stringed instruments; in La signora senza camelie, five saxophones and a piano; in Le amiche, two guitars and a piano; in L’avventura, a small group of wood instruments; in L’eclisse, brass instruments and a piano; in Deserto rosso, voice, song, and electronic music; in Gli sbandati, there is the adoption, extremely modern, of the stringed instruments; in I delfini, “short songs”, among which What a sky, solo for guitar and piano; in Gli indifferenti, solo for trumpet, strings, and piano; in Hiroshima, mon amour, flute, piccolo, piano, clarinet, viola, English horn, double-bass, and guitar. The use he makes of these instruments is often forced, going beyond their natural range of sounds. In this way, therefore, their timbre and registers are modified, making them sound almost like new instruments. Typical example of this way of operating is the percussive utilization of instruments, normally melodic, such as the piano.

- “Musical aphorism”, the adoption of the fragment in disfavour of the “Hollywood traditional thematism”, using the obstinate as “lietmotivica” (where the word leitmotiv is meant in a very strict Wagnerian way, like the elevation of the events to the sphere of their metaphysical meanings )(4). This way of composing, allows him to “atomize” his presence, without interrupting the musical line, and keeping, in this way, a kind of continuity, and leaving the opportunity to create, time after time, some very meaningful improvisations, and to resume, in any moment, the interrupted line. (5)

- “Semantic-Expressive Economy”. Fusco’s music doesn’t “visualize” or underline the images, as it used to happen in the tradition, but he creates the atmosphere, like a light which illuminates, or not, an environment, emphasizing its inner meaning, rather than its formal appearance; it isn’t descriptive, it doesn’t identify the situations, but it evokes some feelings, it is the inside voice or, if you prefer, some kind of psychological introduction, it tells us what, in other ways, we wouldn’t be able to hear; “it accomplishes the function to emotionally reinforce and to accompany the process of the inner talk”.(6) In general, “the pretension to make the music discreet doesn’t work in analogy with noise, but just with triviality”(7) in the specific case, Fusco succeeds in making extra-musical elements as “precipitated” of the music itself, as music may become something else alone, becoming symbol and archetype “sound soul” of the piece, and of the message the director wants to give. (8) A typical example, may be the most successful among the sound-tracks he wrote for Antonioni, is the one he created for L’avventura, where noises, sounds, are taken, elaborated, and integrated with the music, creating an evocative contribution to this director’s drama.

- Counterpoint, also adopting the tonal system and the styles of the classic ages, Fusco’s music succeeds in being modern and present. He takes the patterns and the forms and he breaks them, transforming them in archetypes, then putting them back together, in his language and style. Rather than the vertical and harmonic aspect, he prefers the horizontal one, melodic and polyphonic, with several voices which counterpoint. He renews and tears off the aggregations of tunes, till they become pure sound, “colour” and also largely adopting dissonance. It is not by chance that the composers he prefers, and he takes important composition ideas from, are: Frescobaldi, Bach, Pergolesi, Bartòk, and Stravinskij.

Immediately after the war, the documentary becomes the most immediate means the new generation, stimulated by the power of the events, has to show its opposition and finally, destroy that idyllic atmosphere, in striking contrast with the new age of life of the “white telephones”. Already in 1942, the documentary Comacchio, by the director Fernando Cerchio, with music by Fusco, gives a warning sign of this sense of discomfort, with the movement, slow and relentless, of rhythms in their fusion and in their blending in the contrast between white and black, which will be developed in a clearer way, always through the documentary, by other directors, soon after the war. It is in this period that the person of Giovanni Fusco’s shows himself in all his potential, not only as long experienced musician, talented with that fresh attitude for changes, which makes him the best collaborator and sure reference for the new generations, but also as generous patron. Fusco was also active in the world of business. He founded, with Venturini and Messeri, the FILMS, a production company specialized in documentaries, which had also the ambition to create and produce “musical films”, this last goal soon abandoned, This idea was reconsidered, about 10 years later, when he created the CINELIRICA, where he produced the musical films “Lajo nell’imbarazzo” by G. Donizetti, “La traviata” by G. Verdi and “La Rita” by Donizetti. Besides the revision of the scores, which he was personally making, in some cases he was also responsible for the direction , which he used to sign using the assumed name of Vasco Ugo Finni, or John Welman, this last one created by Carlo Belli, writer and chief editorial of the Tempo’s. It was an extraordinary opportunity that the maestro put at disposal of young generations of singers and movie directors, and that allowed him, using his encouragement, to witness to the beginning of the most promising directors on the Italian movie scenery: Michelangelo Antonioni, to begin with. Immediately after the war, the documentary becomes the most immediate means the new generation, stimulated by the power of the events, has to show its opposition and finally, destroy that idyllic atmosphere, in striking contrast with the new age of life of the “white telephones”. Already in 1942, the documentary Comacchio, by the director Fernando Cerchio, with music by Fusco, gives a warning sign of this sense of discomfort, with the movement, slow and relentless, of rhythms in their fusion and in their blending in the contrast between white and black, which will be developed in a clearer way, always through the documentary, by other directors, soon after the war. It is in this period that the person of Giovanni Fusco’s shows himself in all his potential, not only as long experienced musician, talented with that fresh attitude for changes, which makes him the best collaborator and sure reference for the new generations, but also as generous patron. Fusco was also active in the world of business. He founded, with Venturini and Messeri, the FILMS, a production company specialized in documentaries, which had also the ambition to create and produce “musical films”, this last goal soon abandoned, This idea was reconsidered, about 10 years later, when he created the CINELIRICA, where he produced the musical films “Lajo nell’imbarazzo” by G. Donizetti, “La traviata” by G. Verdi and “La Rita” by Donizetti. Besides the revision of the scores, which he was personally making, in some cases he was also responsible for the direction , which he used to sign using the assumed name of Vasco Ugo Finni, or John Welman, this last one created by Carlo Belli, writer and chief editorial of the Tempo’s. It was an extraordinary opportunity that the maestro put at disposal of young generations of singers and movie directors, and that allowed him, using his encouragement, to witness to the beginning of the most promising directors on the Italian movie scenery: Michelangelo Antonioni, to begin with.

The prolific meeting with Michelangelo Antonioni dates 1948, when they work together for the documentary signed by this director N.U. Nettezza Urbana, located along the streets of Rome, and which sees the maestro also in charge of its production. Fusco had already signed over 40 sound-tracks, including documentaries and feature films, but his meeting with Antonioni is fundamental for his career. By the side of an educated and rigorous author, with also a fine taste for music, Fusco was spurred to consider cinema the location where to wake up, inside himself, the old Casella’s heritage for heavy loads having creative nature, able to transform the character of the composition of music for films from artisan work to an artistic duty, having its own inside value.

The cooperation between Antonioni and Fusco has not been only an artistic cooperation, a cooperation between two artists; it has mostly been a deep and sincere strong friendship, with daily meetings, consideration, successful intuitions, and disputes between two personalities that, even though so different, would perceive one another’s strong possibilities to carry out their expressive beliefs.

Antonioni has been, for Fusco, the perfect incentive, the one who pushed him towards an inside reflection and the personal research in matter of films; for Antonioni, Fusco represents his idea of music for films, which consists in dissolving the pretextuous music language, trying to amplify the extreme ranges of feelings, till they become just a “voice” that “while it’s doing it, nobody talks.”

The musical realization-interpretation by Fusco’s, of Antonioni’s ideas, continues with the documentaries, Superstizione, Sette canne e un vestito, and L’amorosa menzogna of 1949. In 1950, with La villa dei mostri, there is their last cooperation concerning documentaries, and the production of the first feature film, Cronaca di un amore, which allowed the author to win the Silver Ribbon Award for the best music. Leaving apart the usual conventions, Fusco’s music concentrates itself on single instruments or on small groups, having a nature more of chamber music rather than symphonic, to allow the lonely timbres to be defined, progressively tearing them off, till they become pure and essential sounds, connecting them to situations, to atmospheres, and to the conscience of the characters and of the plot, till they inextricably adhere.

All that, was making Fusco, already rigorous and demanding with himself, in the position to hire exceptional players, like the great French saxophone player Marcel Mule, accompanied on the piano by Armando Renzi, for the interpretation of the piece, for sax and orchestra, for Cronaca di un amore. Another fantastic example is the adoption of five saxophones, the “Paris Quintet”, conducted by Mule, for La signra senza camelie (1953), which performs as if it were only one instrument.

In I Vinti (1952), the environment is the setting for the action, in a way to make the director deal, in different ways, with the help of music, with photography and acting. Not by chance, Fusco adopts instruments of clear national nature, like the mandolin, the piano, and the accordion, in a very unheard of, anti-popular way. With this movie, music will stop during the most dramatic moments. For Le amiche, (1955), the musician looks for and creates new armonic solutions, characterized by a solid rhythmic heterogenecity, through the counterpoint between

a guitar, (played by Libero Tosoni), and a piano (played by Armando Trovaioli) with flashes by single instruments.

The score for Grido (1957), written for piano solo, is performed in an incomparable way by the piano player Lya De Barberis. The score is based, mainly, on the elaboration of two pieces, having different character. The diversified sequence of five themes (showing a certain similarity to Ravel’s themes and to melodies from the piano sonatas by Chopin), developed in the weak rotation of a dreaming and melancholy Andantino, almost scholastic, and a Valzer moderato, sharper, with its characteristics slightly modified. Both themes, seem to come from nature, from the outside world, from the fields, from the river banks, from the fog of a scenery which is the tragic portrait of the characters.

In L’Avventura (1960), the architectural design of the film, based more on the aesthetic beauty of the images, rather than on the refinement of words, is ignored by the music, which becomes sort of metaphysic language of the soul.

The sound-track follows the mood and the emotions of the characters, thanks to a sharp and anxious score, with rarefied and unusual timbres, based, mostly, on a concertino of wood and wind instruments, differently combined. There is also room for an unusual mandolin and guitar little orchestra, where jazz memories, pop, and from the Bolero by Ravel, can be recognized. Music, constantly going through rarefaction, becomes a lament and essence of the soul. Silver Ribbon award for the best music.

In Eclisse (1962), the comment adopts sonorous, dissonant fragments, having a metal effect, and ending with nothing concluded, or definitive. For this score, Fusco hires two exceptional artists: the singer Mina, who performs the twist having the same title, and the Maestro Franco Ferrara, engaged to conduct the music of the film.

In Deserto Rosso (1964), the tendency to the “mechanicalism” of music, to its abstraction, is taken further ahead, when Antonioni calls Gelmetti, who, using fragments from his own compositions continues, so to say, the massive presence of noises from refineries, cars, anchored ships; objects, once again, are more important than feelings. In contrast to that, there is just Fusco’s intervention, which basically consists of a “wordless song” , a long vocalism for female voice (performed by the composer’s daughter, Soprano Cecilia Fusco), who supports the sequence of fable-dream. Deserto rosso, awarded with the Leone d’Oro at the XXVth Mostra d’Arte Cinematografica of Venice, is considered, by the world movie criticism, among the best movies produced in the world. With this film, the cooperation between Antonioni and Fusco comes to an end; a rare example of creative osmosis.

Fusco’s fame becomes also international, mostly due to two successful movies by Alain Resnais: Hiroshima mon amour (1959) and La guerre est finie (1966). Fusco’s fame becomes also international, mostly due to two successful movies by Alain Resnais: Hiroshima mon amour (1959) and La guerre est finie (1966).

In Hiroshima mon amour Fusco’s music refuses to follow the dialectic of the shots, fully skipping the “narrative” worries and the “ameublement.” (9) An anti-realistic music, though, which still gets, fully and intimately, in its whole, the meaning of the entire story and creating, all around it, an indefinable atmosphere, almost a lament, even though with a remarkable “psychological depth”. Only eight instruments, conducted by Fusco, are needed to create the sense of present, of eternity, and of the refusal to forget in the expansion of the time of memory. There are no recognizable themes, but only fragments, melodic signs, tied to psychological cores, such as oblivion, the relationship between Nevers-Hiroshima and the present. This film was mentioned with the award “Premio Autori Cinematografici” at the Cannes Festival. (My enthusiasm for your score doesn’t decrease. But, on the contrary, it increases every time I listen to it. I am amazed for the speed, almost diabolic, with which you have succeeded in penetrating the heart of our movie. Without your contribution, this movie would have been exposed to the risk of becoming nothing but a cold dummy, without any real life.“ Extract from a letter by Alain Resnais to Giovanni Fusco, dated May 25th, 1959).

In Guerre est finie, the gentle essentiality of the vicissitudes related to the main character, and portrayed in an elegiac key re-created, like for ancient heroes, through the adoption of voices in a sort of manlike lament.

Fusco’s foreign production doesn’t stop with Resnais, but, among the others, the following must be mentioned: Climats (Restless senses) (1961) by Stellio Lorenzi, Dulcinea, incantesimo d’amore (1962) by Vincenzo Escriva, Rocambole (1963) by Bernard Borderie, Le parias de la gloire (1963) by Henri Decoin and L’aveau (posthumous 1970) by Costi Costa-Gavras, which once again demonstrates the maturity and the peculiarity of Fusco’s language, where the extreme synthesis of a sound made only by a small group can be noticed, trying to produce effects of great relevance.

Through Films of Giovanni Fusco’s, Francesco Maselli realizes his first documentary, Bagnaia, paese italiano, awarded in Venice in 1949, which sees the beginning of the cooperation of this young artist with our musician. Again, in 1951, Maselli is beside Fusco to realize a series of documentaries, in the attempt, successfully carried out, to re-write, using his own language, all the teachings he had received from his maestros, Antonioni and Visconti: Niente va perduto (1951), Fioraie (1952), Festa a Positano (1952) and Bambini (1954). In each of these, Fusco’s music accompanies Maselli’s sight, distant but at the same time participating, without lapsing towards signs of populism or sentimentalism, which were typical of other documentaries. The cooperation between Fusco and Maselli continues with what has been defined, by Stefania Parigi, the trilogy of youth: Gli sbandati (1954), I delfini (1960), and Gli indifferenti (1963); it is not by chance that we find the same style of comment which becomes a further tie for these three movies, and which is also typical of Fusco’s way, that is: a music which is the soul of the character, which tells us what “the character itself doesn’t have the bravery to show us.”

Another very important cooperation is with Damiano Damiani, for whom Fusco was in charge of the music for Il rossetto (1960), awarded at the San Sebastian Festival and, above all, Il giorno della civetta (1968) famous feature film about the intriguing mafia story from the novel by Leonardo Sciascia. The music composed by Fusco for this film remains, even today, one of the most durable and inspired tracks in the movie history about mafia, and it’s become a leader. In fact, it is possible to find some perfect references in several composers who went close to the same topic. The music portrays, in the intimate of the actions, the dichotomy and the contrasts of passions and tragic mixtures among the drought of the scenery, the tastes of the earth, strong and pungent, imbued of culture and backword, of blinding light and cold hearted, in a Mediterranean atmosphere with a clear Arab influence, painted with strong colours.

Close to the rarefied structures, dry, without the life wanted in its integrity we find in Antonioni’s movies, is the musical comment for Il mare, by Giuseppe Patroni-Griffi (1962), and, certainly, Fusco’s music, “educated” and very refined, is definitely superior to the value of the movie it “accompanies”, perhaps we should say it “leads”, without succeeding, though, in elevating it or filling the gaps of the direction and of the arrangement of scenes.

Still to Fusco, also the more committed Taviani brothers, Paolo and Vittorio, applied, for I fuorilegge del matrimonio (1963) and for Sovversivi (1967).

Very beautiful and characteristic, by Fusco is the comment for La corruzione (1963) by Mauro Bolognini. It is recorded between the initial exhibition and the obsessive final performance of a “hully-gully” rhythm.

With the characteristic obsessive poundings of the obstinate Fusco, which indicate the time going by and the moods of the characters, is the comment for L’oro diRoma (1961) by Carlo Lizzani.

Particularly interesting is the score for Violenza segreta (1963) by Giorgio Moser, where Fusco doesn’t let his attention to be diverted by the African atmosphere of the movie, refusing an expected exoticism, underlining instead the “occidentality” of music.

Giovanni Fusco has been the real protagonist of his time, giving his cultural contribution in all fields, from his own ability as famous composer, to activities having social aspects, such as: the foundation of the Music for Films Composers’ Union, with musicians Piero Piccioni, Carlo Rustichelli, and Armando Trovajoli; or the cooperation with the movement of poets, writers, intellectual figures, who were trying, towards the end of the fifties, to write texts and music for the consumption songs, with the aim of raising their quality standard. La ballata del suicidio, on a text by Pier Paolo Pasolini, represents one of the highest examples of this cooperation, between intellectual people and musicians, and to give the Italian song the characteristics of “master’s song”.

The cooperation with Pasolini continues with the composition of the original music for the third episode of the collective movie “Amore e Rabbia” named Le sequenze del fiore di carta (1968) inspired to the evangelic episode “of the innocent fig”, with the introduction of the twist danced by the protagonist.

Cinema, since the end of the war, thanks to some inspired personalities of literature, cinema, and music, pulled away from that place of accidental vision, accompanied by sounds, improves its quality towards a new aesthetic authenticity, able to introduce itself as complex perceptive and cognitive experience, which allows the participation of independent senses, such as eye and ear, in a perfect coincidence of the sensorial spheres: the audiovision.

Many directors and musicians have realized that the translation of the image comes true in a correct syncretism between the sound component and the visual one, where music reinforces what cannot be shown, revealed, unexpressed.

Fusco was the first one to materialize the principles that the new semantic function of music for films had required. A vanguard musician, without being a desecrator, though, always favourable and proposing towards experiments and research, still remaining tied to the tonal system and to the forms of the European tradition, from his 12-note system experience he was able to draw the ability to translate the intimistic accent.

He was able to satisfy any direction need, even the most pretentious ones, like the ones Antonioni used to have. And for whom he stated that he was forgetting to be a composer, in the awareness that his was not a position of subordination, but a necessary tribute to the improvement of the quality of music for films and, so, to open wider expressive horizons to it.

“Films without music cannot be made. Music is the light, the soul, of the film. It is the voice of the mystery hiding in the depth of the image.”(Fusco). If music for films, in the fifties, began to be considered one of the most characteristic applications of our times, was due to people like Fusco, who re-habilitated it from the refusal where it had been confined since the beginning of the movie history, because it was believed to have less aesthetic value and to be incapable to stand any confrontation with the “classic” production.

For Giovanni Fusco, cinema is an authentic vocation which expresses itself in its instinctive and secret intuition, and in its immediate creative adaptability, which has been able to give back to the image the amplified vision of the mind.

“The oldest specialist in music for films, in his good-natured aspect, plump, not very tall, friendly, with blue eyes, often flashed with impalpable irony, at first sight, more than an artist, he may have looked like a teacher, a boring one, calm, philosopher for his natural good qualities, and wisdom.”

In addition to these descriptions, written by critics who have interviewed him and that seem to portray an exterior image of “just another man”, there is the shocking reality to be in front of a musical genius who taught, and still teaches, that great masterpieces could be created even without too much freedom, in opposition to what it was believed among the circles of “educated music”, where the meaning of freedom was still tied to the ancient romantic idea of creativity. Giovanni Fusco has been a restless artist, always in favour of the new, a “modern” artist, and of impressive actuality. Leader in the music for films, it is not by chance that he was defined, by Resnais, “A creating movie maker”, an artist still to be discovered and, despite his sudden death, due to a heart attack in the night of May 31st, 1968, he is a voice still not extinguished.

|

| |

|

GIOVANNI FUSCO

GIOVANNI FUSCO During the years of Fusco’s youth, in the period between the two wars, the Italian music scene was going through an exciting reformation movement, due mostly to the “eighty’s generation”, which included Respighi, Pizzetti, Casella, Malipiero, and a certain number of less important authors. Certainly, Casella was the ensign of this renewal movement, which was hoping to elevate the Italian musical culture, trying to bring it inside a larger European scenery. Casella himself had all the talents of the composer, theoretic, and pianist, and he had deeply understood, clearer than his colleagues had, that the modification of the way of life of the human communities was also modifying the ways and the kinds of their sensorial perception. For Fusco, to meet this great artistic personality was very useful, either for the acquisition of the theoretic basis about the nature of the musician, based on humble and conscious handicraft, even though of a “superior handicraftsman”, like the great figures of the Renaissance, conscious of his function, and for the opening towards what was new, towards a world which was fastly changing, and that makes him, fearless, with audacity, try all kinds of new experiences and experimentations. From this maestro, Fusco will adopt, mostly, his courage and ability to retake other author’s styles, keeping unchanged, in their forms, a clear plasticity of the musical figurations, a deep iconicity, playing among polytonal solutions, rhythmic vibrations, rhythms taken from the most dissimilar musical kinds, such as Fox-Trott, Jazz, and the “consumption music” that, up to those days, had found the hostility of the official academic milieu, and also arriving to introduce some electronic experimentations.

During the years of Fusco’s youth, in the period between the two wars, the Italian music scene was going through an exciting reformation movement, due mostly to the “eighty’s generation”, which included Respighi, Pizzetti, Casella, Malipiero, and a certain number of less important authors. Certainly, Casella was the ensign of this renewal movement, which was hoping to elevate the Italian musical culture, trying to bring it inside a larger European scenery. Casella himself had all the talents of the composer, theoretic, and pianist, and he had deeply understood, clearer than his colleagues had, that the modification of the way of life of the human communities was also modifying the ways and the kinds of their sensorial perception. For Fusco, to meet this great artistic personality was very useful, either for the acquisition of the theoretic basis about the nature of the musician, based on humble and conscious handicraft, even though of a “superior handicraftsman”, like the great figures of the Renaissance, conscious of his function, and for the opening towards what was new, towards a world which was fastly changing, and that makes him, fearless, with audacity, try all kinds of new experiences and experimentations. From this maestro, Fusco will adopt, mostly, his courage and ability to retake other author’s styles, keeping unchanged, in their forms, a clear plasticity of the musical figurations, a deep iconicity, playing among polytonal solutions, rhythmic vibrations, rhythms taken from the most dissimilar musical kinds, such as Fox-Trott, Jazz, and the “consumption music” that, up to those days, had found the hostility of the official academic milieu, and also arriving to introduce some electronic experimentations. Soon after the end of the war, Maestro Fusco appeared several times, as conductor of concerts of contemporary music, dedicating him self also to the performance of jazz music in American clubs. His remarkable ability of playing at sight, was helping him in doing that; and, he was often proving it during the evenings spent with his musicians friends, where he used to perform for this audience, playing at sight, just printed, the musics by Stokausen or Stravinskij. Beginning these days, other important works deserve to be mentioned, as the Sonata a due, for violin and cello, the Suite Americana, for orchestra, the Sonata a tre, for violin, flute, and clarinet, the Psalm 112, for 4 soloist voices, 2 guitars, and jazz battery, dedicated to Goffredo Petrassi, the Suite for eight instruments, from the movie “Hiroshima mon amour”, the Fantasia da concerto, for violin and string instruments, the Piccolo concerto, for clarinet and orchestra, the Tam Tam of the Animals, for children’s voices and 5 instruments, the Canzone dell’uccellaio, for basso and orchestra, the Sinfonia Italiana, for orchestra, and the unpublished ballet La Rapina, on a subject written by Michelangelo Antonioni, commissioned by the Opera Theater “La Scala” in 1965, and never performed, because of the sudden death of the Maestro. La Rapina is the portrait of the inhabitants living in a neighbourhood outside a city, where the main characters of the ballet go through constant fights and quarrels: “which suddenly start and suddenly end”. Even in this ballet, music is responsible for the intimate expression, deeply plastic, of every represented reality: from the objective one to the one unspeakable of the characters involved.

Soon after the end of the war, Maestro Fusco appeared several times, as conductor of concerts of contemporary music, dedicating him self also to the performance of jazz music in American clubs. His remarkable ability of playing at sight, was helping him in doing that; and, he was often proving it during the evenings spent with his musicians friends, where he used to perform for this audience, playing at sight, just printed, the musics by Stokausen or Stravinskij. Beginning these days, other important works deserve to be mentioned, as the Sonata a due, for violin and cello, the Suite Americana, for orchestra, the Sonata a tre, for violin, flute, and clarinet, the Psalm 112, for 4 soloist voices, 2 guitars, and jazz battery, dedicated to Goffredo Petrassi, the Suite for eight instruments, from the movie “Hiroshima mon amour”, the Fantasia da concerto, for violin and string instruments, the Piccolo concerto, for clarinet and orchestra, the Tam Tam of the Animals, for children’s voices and 5 instruments, the Canzone dell’uccellaio, for basso and orchestra, the Sinfonia Italiana, for orchestra, and the unpublished ballet La Rapina, on a subject written by Michelangelo Antonioni, commissioned by the Opera Theater “La Scala” in 1965, and never performed, because of the sudden death of the Maestro. La Rapina is the portrait of the inhabitants living in a neighbourhood outside a city, where the main characters of the ballet go through constant fights and quarrels: “which suddenly start and suddenly end”. Even in this ballet, music is responsible for the intimate expression, deeply plastic, of every represented reality: from the objective one to the one unspeakable of the characters involved. Immediately after the war, the documentary becomes the most immediate means the new generation, stimulated by the power of the events, has to show its opposition and finally, destroy that idyllic atmosphere, in striking contrast with the new age of life of the “white telephones”. Already in 1942, the documentary Comacchio, by the director Fernando Cerchio, with music by Fusco, gives a warning sign of this sense of discomfort, with the movement, slow and relentless, of rhythms in their fusion and in their blending in the contrast between white and black, which will be developed in a clearer way, always through the documentary, by other directors, soon after the war. It is in this period that the person of Giovanni Fusco’s shows himself in all his potential, not only as long experienced musician, talented with that fresh attitude for changes, which makes him the best collaborator and sure reference for the new generations, but also as generous patron. Fusco was also active in the world of business. He founded, with Venturini and Messeri, the FILMS, a production company specialized in documentaries, which had also the ambition to create and produce “musical films”, this last goal soon abandoned, This idea was reconsidered, about 10 years later, when he created the CINELIRICA, where he produced the musical films “Lajo nell’imbarazzo” by G. Donizetti, “La traviata” by G. Verdi and “La Rita” by Donizetti. Besides the revision of the scores, which he was personally making, in some cases he was also responsible for the direction , which he used to sign using the assumed name of Vasco Ugo Finni, or John Welman, this last one created by Carlo Belli, writer and chief editorial of the Tempo’s. It was an extraordinary opportunity that the maestro put at disposal of young generations of singers and movie directors, and that allowed him, using his encouragement, to witness to the beginning of the most promising directors on the Italian movie scenery: Michelangelo Antonioni, to begin with.

Immediately after the war, the documentary becomes the most immediate means the new generation, stimulated by the power of the events, has to show its opposition and finally, destroy that idyllic atmosphere, in striking contrast with the new age of life of the “white telephones”. Already in 1942, the documentary Comacchio, by the director Fernando Cerchio, with music by Fusco, gives a warning sign of this sense of discomfort, with the movement, slow and relentless, of rhythms in their fusion and in their blending in the contrast between white and black, which will be developed in a clearer way, always through the documentary, by other directors, soon after the war. It is in this period that the person of Giovanni Fusco’s shows himself in all his potential, not only as long experienced musician, talented with that fresh attitude for changes, which makes him the best collaborator and sure reference for the new generations, but also as generous patron. Fusco was also active in the world of business. He founded, with Venturini and Messeri, the FILMS, a production company specialized in documentaries, which had also the ambition to create and produce “musical films”, this last goal soon abandoned, This idea was reconsidered, about 10 years later, when he created the CINELIRICA, where he produced the musical films “Lajo nell’imbarazzo” by G. Donizetti, “La traviata” by G. Verdi and “La Rita” by Donizetti. Besides the revision of the scores, which he was personally making, in some cases he was also responsible for the direction , which he used to sign using the assumed name of Vasco Ugo Finni, or John Welman, this last one created by Carlo Belli, writer and chief editorial of the Tempo’s. It was an extraordinary opportunity that the maestro put at disposal of young generations of singers and movie directors, and that allowed him, using his encouragement, to witness to the beginning of the most promising directors on the Italian movie scenery: Michelangelo Antonioni, to begin with. Fusco’s fame becomes also international, mostly due to two successful movies by Alain Resnais: Hiroshima mon amour (1959) and La guerre est finie (1966).

Fusco’s fame becomes also international, mostly due to two successful movies by Alain Resnais: Hiroshima mon amour (1959) and La guerre est finie (1966).